Execution of Sambhaji

| Part of Deccan wars | |

Mughal Forces capture Sambhaji | |

| Date | 19 February – 11 March 1689 |

|---|---|

| Duration | Three weeks |

| Venue | Tulapur arch |

| Location | Tulapur |

| Coordinates | 18°40′10″N 73°59′44″E / 18.6694°N 73.9955°E |

| Type | Execution by beheading |

| Cause |

|

| Reporter | Khafi Khan Ishwar Das |

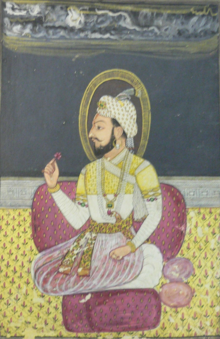

| Organized by | Mughal empire |

| Outcome | Death of Sambhaji |

| Arrests | Sambhaji, Kavi Kalash and twenty-five Maratha officers |

| Convicted |

|

The Execution of Sambhaji was a significant event in 17th-century Deccan India, where the second Maratha King was put to death by order of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb. The conflicts between the Mughals and the Deccan Sultanates, which resulted in the downfall of the Sultanates, paved the way for tensions between the Marathas and the Mughals. Following the death of Shivaji, his son Sambhaji ascended to the throne and conducted several campaigns against the Mughals. This led Aurangzeb to launch a campaign against the Marathas, resulting in the capture of the Maratha King by the Mughal general Muqarrab Khan. Sambhaji and his minister Kavi Kalash were then taken to Tulapur, where they were tortured to death.

Background

[edit]

Sambhaji, the son of the first Maratha King Shivaji, faced imprisonment during his father's reign due to his irresponsible behavior and indulgence in sensual pleasures. Shivaji took the step to arrest him. Sambhaji managed to escape from the Panhala fort, where he was held captive, and sought refuge with the Mughal forces under Diler Khan. However, he soon realized that Diler Khan intended to send him to Delhi as a prisoner, prompting Sambhaji to return. Upon his return, he was once again captured by the Marathas.[1][2]

After Shivaji's death, Sambhaji escaped from the Panhala fort and proclaimed himself king, eliminating all of Shivaji's ministers who opposed his succession.[3] Once on the throne, Sambhaji waged numerous campaigns against the Mughals, following in his father's footsteps. However, unlike Shivaji, he condoned the atrocities committed by his army. During his raid of Burhanpur, the inhabitants of the fort endured rape, torture, and robbery.[4] To the Nobles of Burhanpur, Sambhaji's raid was more than just a disruption of public order; it was seen as an attack on the Muslim community by a non-believer. If the Mughal Empire failed to protect the lives and property of Muslims, it was believed that Aurangzeb's titles as ruler should not be acknowledged during the Friday congregational prayers. Under pressure from the Marathas and Aurangzeb's rebellious son, Akbar, Aurangzeb launched a campaign towards the Deccan region.[4]

During the Mughal siege of Golconda and Bijapur, Muslim Ulema from Bijapur questioned Aurangzeb about how he could justify waging war against fellow Muslims. Aurangzeb's response was that the Sultan had harbored and aided Sambhaji, who had been causing harm to Muslims across the region. Aurangzeb also condemned Abul Hasan for the additional offense of relinquishing control of his state to his two Brahmin ministers.[4] The fall of the Deccan Sultanates marked the beginning of a new chapter in Deccan history known as the "Deccan Wars.".[5]

Capture of Sambhaji

[edit]While Aurangzeb was besieging Golconda and Bijapur, Sambhaji observed his movements from the fort of Panhala. Following the capture of Bijapur and Golconda, a significant amount of wealth and military resources fell into Mughal hands. After seizing these two key forts, Aurangzeb deployed Sarja Khan, a seasoned general from Bijapur familiar with the Deccan terrain.[6]

In December 1687, the Battle of Wai unfolded between the Maratha forces under the command of Hambirrao Mohite, dispatched by Sambhaji, and the Mughal forces led by Sarja Khan. Despite the Maratha forces emerging victorious, Mohite tragically lost his life to a cannonball during the conflict.[7] Sambhaji's military strength dwindled after the battle, prompting him to relocate with a smaller contingent of soldiers. His camp faced encirclement by Mughal agents within the confines of the Raigarh and Panhala hills. The Maratha faction led by Soyarabai and the Shirkes betrayed Sambhaji by divulging his movements to the Mughals, resulting in the revelation of Sambhaji's whereabouts. They provided daily updates on his movements to the Mughals, ultimately leading to Sambhaji's failure to safeguard himself, despite his efforts to protect the kingdom.[8]

Sambhaji was caught off guard by the Mughal commander Muqarrab Khan, resulting in a battle at Samgamneshwar where the Marathas suffered casualties, leading to their defeat. Five Marathas were killed, and the remaining fled. Sambhaji's minister, Kavi Kalash, was captured, while Sambhaji himself managed to escape and seek refuge in a temple. However, the Mughals discovered his hiding place, and despite his attempts to flee, Sambhaji was apprehended on February 1, 1689.[9] Thus the Mughals captured Sambhaji, his minister Kavi Kalash, and twenty-five other officers.[8][10] Muqarrab Khan transported them to Akluj, where Aurangzeb was. Upon receiving the news of their capture, Aurangzeb was pleased and renamed the place Asadnagar to commemorate the event.[9]

Execution

[edit]

The two prisoners, Kavi Kalash and Sambhaji, were taken to the Imperial encampment near the Bhima river. Despite Sambhaji's royal status, he was not accorded the same respect as the Mughals granted to the rulers of Bijapur and Golconda. Instead, he and his ministers were humiliated by being dressed as buffoons in long fool's caps with bells attached, mounted on a camel, and paraded through the Mughal camps amidst the beating of drums and the pealing of trumpets. They were then presented to Aurangzeb, who was offering a thanksgiving prayer.[11][10]

Accounts vary as to the reasons for what came next:

Mughal accounts state that Sambhaji was asked to surrender his forts, treasures and names of Mughal collaborators with the Marathas and that he sealed his fate by insulting both the emperor and the Islamic prophet Muhammad during interrogation and was executed for having killed Muslims.[12] The ulema of the Mughal Empire sentenced Sambhaji to death on-allegations of the atrocities his troops perpetrated against Muslims-in Burhanpur, including plunder, killing, dishonour and torture.[13]

Maratha accounts instead state that he was ordered to bow before Aurangzeb and convert to Islam and it was his refusal to do so, by saying that he would accept Islam en the day Aurangzeb presented him his daughter's hand, that led to his death.[14] By doing so, he earned the title of "Dharmaveer" ("protector of dharma").[15]

Other accounts state that Sambhaji challenged Aurangzeb in open court and refused to convert to Islam. Dennis Kincaid writes, "He (Sambhaji) was ordered by the Emperor to embrace Islam. He refused and was made to run the gauntlet of the whole Imperial army. Tattered and bleeding he was brought before the Emperor and repeated his refusal. His tongue was torn and again the question was put.[15][16][17] He called for writing material and wrote 'Not even if the emperor bribed me with his daughter!" So then he was put to death by torture."[15]

Some accounts state that Sambhaji's body was cut into pieces and thrown into the river or that the body or portions were recaptured and cremated at the confluence of the rivers at Tulapur.[18][19] Other accounts state that Sambhaji's remains were fed to the dogs.[20][page needed]

Aftermath

[edit]

During his reign, Sambhaji was unable to accomplish much for his people. However, his death elevated him to the status of a martyr.[11] Sambhaji's son, Shahu, was held captive by Aurangzeb and was only released when he reached maturity.[16] Following these events, the Mughals reached their peak in terms of territorial expansion, establishing their farthest extent in the subcontinent. Despite this, conflicts between the Marathas persisted. Rajaram, the brother of Sambhaji, sought refuge in the Jinjee fort in the south, while Maratha officers continued their raids in the northern Deccan region.[4]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Mehta 2005, p. 47.

- ^ Bhave, Y. G. (2000). From the Death of Shivaji to the Death of Aurangzeb: The Critical Years. Northern Book Centre. p. 35. ISBN 978-81-7211-100-7.

- ^ Sharma, Sunita (2004). Veil, Sceptre, and Quill: Profiles of Eminent Women, 16th- 18th Centuries. Khuda Bakhsh Oriental Public Library. p. 139.

- ^ a b c d Richards 1993, pp. 217–223

- ^ Richards 1993, p. 225.

- ^ Karandikar, Shivaram Laxman (1969). The Rise and Fall of the Maratha Power. Sitabai Shivram Karandikar. pp. 307–310.

- ^ Joshi, Pandit Shankar (1980). Chhatrapati Sambhaji, 1657-1689 A.D. S. Chand. p. 241.

- ^ a b Mehta 2005, pp. 49–50.

- ^ a b Kulkarni, G. T. (1983). The Mughal-Maratha Relations: Twenty Five Fateful Years, 1682-1707. Department of History, Deccan College Post-Graduate Research Institute. p. 74.

- ^ a b Richards 1993, p. 223.

- ^ a b Mehta 2005, p. 50.

- ^ Richards, John F. (2010). The Mughal empire. The new Cambridge history of India / general ed. Gordon Johnson 1, The Mughals and their contemporaries (Transferred to digital print ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2.

- ^ Hasan, Farhat (May 1995). "The New Cambridge History of India, I.5- The Mughal Empire. By. John F. Richards. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1993. Pp. xv, 320". Modern Asian Studies. 29 (2): 441–447. doi:10.1017/s0026749x00012816. ISSN 0026-749X.

- ^ Bhattacherje, Satya Bikash (2008). Encyclopaedia of Indian events & dates (6., rev. ed.). New Delhi: Sterling Paperbacks. ISBN 978-81-207-4074-7.

- ^ a b c Bhave, Yeshwant Gopal (2000). From the death of Shivaji to the death of Aurangzeb: the critical years. New Delhi: Northern Book Centre. ISBN 978-81-7211-100-7.

- ^ a b Johnston, Harry (1986). The Great Pioneer in India, Ceylon, Bhutan & Tibet. Mittal Publications. p. 252.

- ^ Pāṭīla, Śālinī (1987). Maharani Tarabai of Kolhapur, C. 1675-1761 A.D. S. Chand & Company. pp. 46–48. ISBN 978-81-219-0269-4.

- ^ Bharati, Rahul Kailas (12 June 2024). A Comprehensive Guide To Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) In Cyberspace. San International Scientific Publications. doi:10.59646/ipr/212. ISBN 978-81-974075-5-0.

- ^ "Election 2012: A Win For Health Reform, But Much Work Remains". Forefront Group. 7 November 2012. doi:10.1377/forefront.20121107.025179. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- ^ Mehta 2005.

References

[edit]- Mehta, Jaswant Lal (1 January 2005). Advanced Study in the History of Modern India 1707-1813. Sterling Publishers. ISBN 978-1-932705-54-6.

- Richards, John F. (1993). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press. pp. 217–223. ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2.